A Canadian soldier fighting in Afghanistan, injured in an attack, is plunged into a timeless world of ancient warriors and mythical creatures. In this dream landscape of his unconscious, guided by a former teacher, he navigates the hero’s journey as described in the ancient poem Beowulf. Post conflict, haunted by his combat experiences, he turns again to this timeless tale of monsters and heroes to understand the stories we tell of war, seeking the truth behind the hero’s mask.

We are all caught in the gyre of war, and never wise enough to acknowledge the inevitable reckoning with history that is demanded as we stand again and again at the pinnacle of crisis. How do we face with necessary courage the failure of the politics that positions us time and time again on the precipice of war? When will we open our eyes and truly see the men and women who return with the invisible scars of battle, and the plight of the innocents left to bury their too soon dead.

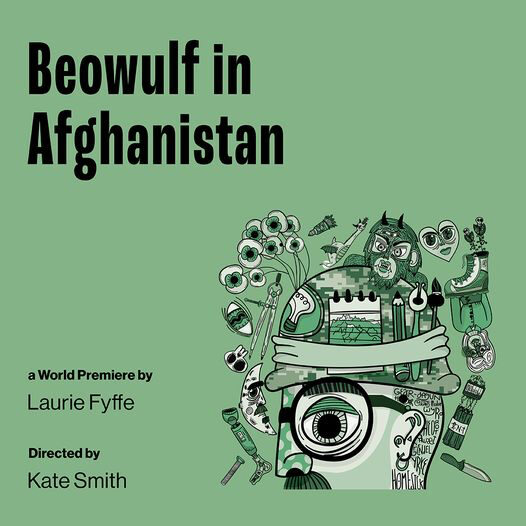

In Beowulf In Afghanistan, Grant, a solider, journeys through post-conflict stress through the lens of a poem written in a resolutely ancient tongue. His vision of Beowulf as a hero is irreconcilable with reality as he stands vulnerable and alone facing what has been done to him on the battlefield, and what he has been a part of doing.

When Beowulf was written three thousand or so years ago there was of course no war in Afghanistan, so there are no direct correlations between the poem and a complex modern conflict. Audiences will perceive connections as a result of their knowledge, loyalties, perceptions, or lived experience. But as he views an ancient world through a modern lens Grant in effect becomes Beowulf and thus in the warrior’s moment of triumph discovers a fatal flaw in the hero myth.

The discovery of that fatal flaw in the hero myth is what led me to the extended version of the play I have written for GCTC’s Tributary project and eventually its Mainstage 2024-2025 Season.

War in the 21st century yields few victories. The lesson of history over centuries of conflicts bleeding into each other is that the better we get at fighting wars the greater the irreparable and indiscriminate damage inflicted on us all. If we learned better how to avoid war, we might yet achieve victory over the dragon. Instead, we feed our dragons the oxygen of our animosities, and in return, they breathe fire.

Acknowledgments & Thanks:

Beowulf In Afghanistan has an extensive bibliography of research. I also wish to extend my sincere thanks to the Canadian Association of Security & Intelligence Studies (CASIS), Greg Fyffe (Past President of CASIS), Sarah Kitz for her excellent dramaturgy, GCTC for the Tributary Project, and my exhaustively imaginative and diligent director Kate Smith. A since thank you also to artists involved in the creation of this play and its journey: Axandre Lemours, Damien Brooms, Julie LeGal, and Lydia Talajic.

Ticket for Beowulf In Afghanistan at GCTC: https://www.gctc.ca/shows/beowulf